The recycling industry is a fascinating topic. Wait! Hear me out before you shake your head and move on.

The fact is that this industry, whether we like it or not, exerts an enormous influence on how our society conducts itself. In many respects, it has been hijacked by forces beyond its control–trotted out as the savior of the planet’s waste crisis and our myriad environmental woes.

In recent years, the pendulum has swung in the other direction with the recycling industry increasingly vilified as the Bad Boy of a greenwashed environmental initiative and obedient servant to Big Oil and Plastic.

The reality is more nuanced, but a clear picture of this complex industry–warts and all–is essential for reconstructing recycling into an effective tool for tackling pollution.

Busting the Recycling-is-Environmental Narrative

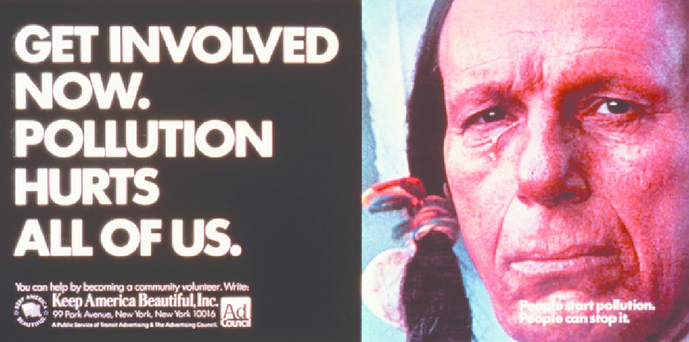

When you think of recycling, recycling symbols or blue bins likely pops into your mind. If you’re a bit older, you’ll remember Keep America Beautiful’s “Crying Indian” ad with his anguished pleas for people to stop littering.

This is the image of recycling we’ve been conditioned to see: a feel-good, pollution-busting initiative that sprouted organically from the grassroots environmental revolution of the 1970s. Folded neatly into this movement, recycling has assumed the mantle of a wise coach leading a polluting populace towards the victory of a clean, green America.

Recycling is More Than Blue Recycling Bins

The reality is that the recycling industry is much more than recycling bins and symbols, and far older than the 1970s Keep America Beautiful campaign–an industry-funded crusade that pinned the blame on consumers for plastic pollution while promoting recycling as an environmental solution.

The process of turning waste into new products is one that has been in practice across the globe for centuries with the first instance of paper recycling documented in the 9th century in Japan. In this country, we can trace recycling back to the 1690 opening of Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Mill to recycle linens and cotton rags.

Fast forward to today, and the industry has expanded beyond paper and linens to include virtually any substance, from timber to sewage water. The more common recyclable materials are glass, aluminum, steel, cardboard, and plastic bottles. Even food waste recycling has seen an uptick in recent years.

Recycled material is used to create a dizzying and diverse set of products, a sampling (by no means exhaustive) of which I include here: clothing and other textiles, appliances, computers, batteries, composted soil, paint, biodiesel, tires, flooring, plastic bottles, building materials, lighting, vehicles, and (of course) aluminum beverage cans.

As you’d imagine, the recycling industry today plays an important part in the nation’s economy–it’s a $100 billion industry that employs close to 700,000 jobs and generates over $5 billion in tax revenue.

Recycling is a Business

The bottom line is that recycling is a profit-making business, not an environmental movement. To be sure, when it’s done right, recycling can yield environmental benefits, but the main industry driver is demand for a particular recyclable substance. If there’s a robust resale market for that substance, then it will be recycled.

When there’s a downturn in prices, recycling businesses will react to preserve their bottom line–even if the consequences are environmentally detrimental. That’s why, for instance, even easily recyclable plastic resins, such as PET plastic, have low recycling rates primarily because newly made “virgin” plastic is currently cheaper than recycled PET.

The Recycling Industry: Problems

Perpetuating Myths

Whether it’s intentional or not, some of the most common myths related to recycling are good for business. They perpetuate the myth that recycling is the one and only waste-buster. Here are the most common myths. For detailed myth-debunking, see Green That Life’s post on common recycling myths.

Everything is Recycled. It’s important to understand the distinction between “recycling”–the process of converting waste into a useful product–and “recyclable”–an item that can be recycled. Just because you place a recyclable item in the recycling bin, doesn’t mean it’ll actually be recycled. More often than not, recyclables do not end up being recycled.

The recycling symbol means an item can and will be recycled. Only part of this statement is true: The recycling symbol only asserts an item’s recyclability, not whether it will actually be recycled.

Recycling rates vary dramatically across materials and across countries. Synthetic turf fields, for example, can be recycled, but the current market for recycled turf is limited, so unwanted turf more likely ends up being incinerated or tossed in landfills.

The irony is that while most of us are–and should be–fixated on plastic recycling, plastic, in all its various forms is one of the trickier materials to recycle. The flimsier a plastic product, the more difficult it is to recycle, and items made from composite material, like plastic snack bags or plastic laminated to-go beverage cups, are nearly impossible to recycle. This is just one of the reasons for plastic’s persistently low recycling rates.

Recycling is the most effective waste reduction tool. Due to a number of factors that include the volatility of a commodity market (see below), consumer confusion (or, wish-cycling), technological challenges, and China’s 2018 policy (aka “National Sword“) that effectively bans most of our recyclables, recycling is not the most effective tool for waste reduction. The overall recycling rate in this country hovers around 32%, while plastic recycling ekes out a dismal 9%.

A Bad Rap

In the last few years as recycling has been exposed as a pawn of the plastics and packaging industries, the process has lost its credibility as an effective waste management tool. This bad rap has been compounded by National Sword, which caused the market to tank and recycling rates to plummet as facilities closed and municipalities discontinued recycling programs.

The result: a growing trend that discounts the entire process and an onslaught of negative press proclaiming that recycling is “dead,” “a lie,” “broken,” and is “at its end.”

The Volatility of a Commodity Market

China’s National Sword and other market forces, including the pandemic, have sent the recycling industry into a tailspin, but it is by no means dead.

As the industry dusts itself off from the last dip in the market, business is returning to a steady pace, but the unpredictable nature of these commodities slams up against the environmental goals of a consistent and robust mechanism for pollution control.

How can the industry deliver on environmental goals of waste reduction–most critically, plastic waste reduction–when the next market dip could be right around the corner? As it is, plastic waste is at catastrophic proportions, and relying on an unpredictable process, is not the solution to waste reduction.

An Industry at Cross Purposes With Environmental Goals

The recycling industry as it currently functions is incapable of stemming the tide of waste–most notably single-use plastic waste–generated by businesses and people. Plastic pollution continues to reach staggering levels and is nearing an irreversible tipping point.

But that’s not a problem for the industry to solve. Indeed, the recycling industry depends on a steady flow of inputs (our unwanted items) to profit and survive. An effective environmental response to our pollution crisis is also at cross-purposes with plastic (aka oil and gas) producers and packaging manufacturers’ business models, despite their best efforts to convince you otherwise.

The Keep America Beautiful campaign is just one in a slew of public relations initiatives by the plastics-focused industries to preserve profits by misleading the public about the efficacy of recycling. All along, these industries had “serious doubt” about the viability of recycling.

The Recycling Industry: Opportunities

Recycling has its problems, but it has the potential to play a role in a retooled waste reduction campaign. It just can’t be relied on in its present state as the only tool and it must be viewed objectively: not as part of an environmental movement, but as a business with services that, when properly employed, can be enlisted as one method for managing waste.

Managing Consumption: Reduce First, Then Recycle

As consumers, we’ve been led to believe that we’re the main cause for our waste crisis, and that’s simply not true, but we can participate by reducing how much we purchase, reusing what we have, recycling right, and helping transform our consumer-focused culture through personal lifestyle changes.

Managing Production: Making Manufacturers Accountable

While the recycling industry should innovate and expand to meet the ever-growing mountain of waste, it is the responsibility of manufacturers, nudged (to put it mildly) by consumers and lawmakers, to promote a circular system by taking into account the environmental footprint of a product’s full lifecycle. This will mean a concerted effort by producers to minimize packaging and favor recycled content.

Although slow, some companies are responding to public pressure. PepsiCo just announced that it will begin to reduce the use of virgin plastic and expand its SodaStream sparkling-water business in an effort to combat plastic waste. Others are working to ease the recycling process and address excessive packaging, like SKC’s EcoLabel, the first fully recyclable shrink film.

More rapid and effective change can be made if lawmakers step up to pass substantive regulations and laws. We’re seeing real progress in some states with the recent passage of extended producer responsibility laws for plastic packaging and California’s full slate of recycling and waste-related laws, which are some of the most ambitious in the country.

At the federal level, sadly, there’s a lot of talk and not much action.

The Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act could transform the recycling system and increase producer accountability, but it sits still in committee. Another recently introduced bill would promote recycled content. One reason that virgin plastic is price competitive is the continued subsidization of fossil fuel production. The REDUCE Act would establish a fee on virgin plastic production to level the playing field for recycled plastic and provide a new source of funding to pay for improvements to America’s recycling and waste management infrastructure.

Progress, yes … but will it be enough to reverse the escalating piles of pollution that blankets our planet?