In an attempt to prove their commitment to helping save the planet from catastrophic global warming, corporate America is abloom these days with net zero pledges. Hundreds of companies of all sizes and from every sector have made some form of net zero climate pledge in the past few years. Armed with splashy, nature-laced ad campaigns, these businesses have proudly revealed their detailed plans to decarbonize operations through various greenhouse gas emissions reduction measures.

All these developments sound promising, particularly since the private sector’s activities contribute significantly to global warming: A mere 90 companies are responsible for two-thirds of historical emissions. But what exactly is a net zero climate pledge, and how effective are these corporate commitments?

What is a Net Zero Climate Pledge?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change defines net zero as that state when “anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere are balanced by anthropogenic removals over a specified period.”

Simply put, attaining net zero emissions means that residual, or unavoidable, greenhouse gas emissions emitted by an entity–person, company, nation–are canceled out by mechanisms that absorb or offset those emissions. So, when a company makes a pledge of net zero emissions by a future date, it is committing to achieving a balance of zero emissions in its operations by that date.

Following the Paris Agreement’s goal of rapid decarbonization to limit global warming to a preferred 1.5 degrees Celcius (compared to pre-industrial levels), many companies have targeted 2050 as their net zero target date. This is the date by which climate scientists believe the world must achieve carbon neutrality in order to avoid the catastrophic effects of human-caused climate change.

The key point to remember is that making a net zero pledge is not the same as making a pledge to end activities that produce greenhouse gas emissions. Think of a net zero corporate pledge as more like an emissions management program that allows continued emissions but removes them from business operations via other means.

At its best, a net zero program can achieve zero emissions through various effective emissions-reduction measures. At its worst, it’s a shell game that cleverly obfuscates continued, business-as-usual emissions.

Types of Net Zero Climate Pledges

To date, there is no standardized net zero climate pledge. Businesses can tailor their own pledge, and/or sign on to a growing number of groups and entities that have been formed to codify corporate commitments.

Notable alliances and groups include the following:

The Climate Pledge is an alliance of companies founded by Amazon and Global Optimism that pledges to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2040. To date, 217 companies and organizations have committed to The Climate Pledge, which requires them to agree to 1) regular reporting of their greenhouse gas emissions, 2) implement decarbonization strategist in line with the Paris Agreement, and 3) take action to neutralize any remaining emissions with credible and substantive carbon offsets.

The Travel Industry’s commitment to decarbonization is reflected by the Glasgow Declaration for Climate Action in Tourism, in which over 300 signatories have agreed to “measure, decarbonize, regenerate and unlock finance” and “deliver a concrete climate action plan, or updated plan, within 12 months of signing.” Other travel-industry pledges to decarbonize by 2050 include members of the International Air Transport Association and the Cruise Lines International Association.

Science Based Targets Initiative, a partnership between CDP, the United Nations Global Compact, World Resources Institute and the World Wide Fund, assists companies with setting science-based emissions reduction targets. To date, 2,000 companies worldwide have set emissions reduction targets through SBTi.

The UN-supported Race To Zero campaign is “the largest alliance of non-state actors committing to achieving net zero emissions before 2050,” and is represented by over 5,000 businesses. It recently released a refined criteria and interpretation guide, establishing minimum standards for net zero initiatives.

Mission Possible Partnership is an alliance of organizations and CEOs from seven of the highest-emitting industries that are “focused on supercharging decarbonization across the entire value chain of [these industries] in the next 10 years.”

The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero is a global coalition of over 450 financial institutions that have pledged net zero goals for 2050 for their businesses, including lending and investing.

Tools for Emissions Removal and Offset

Companies employ a variety of tools to achieve net zero emissions, but the key to an effective corporate sustainability strategy is one that measures and removes emissions across its entire value chain.

Some of the carbon removal tools that companies can employ include the following:

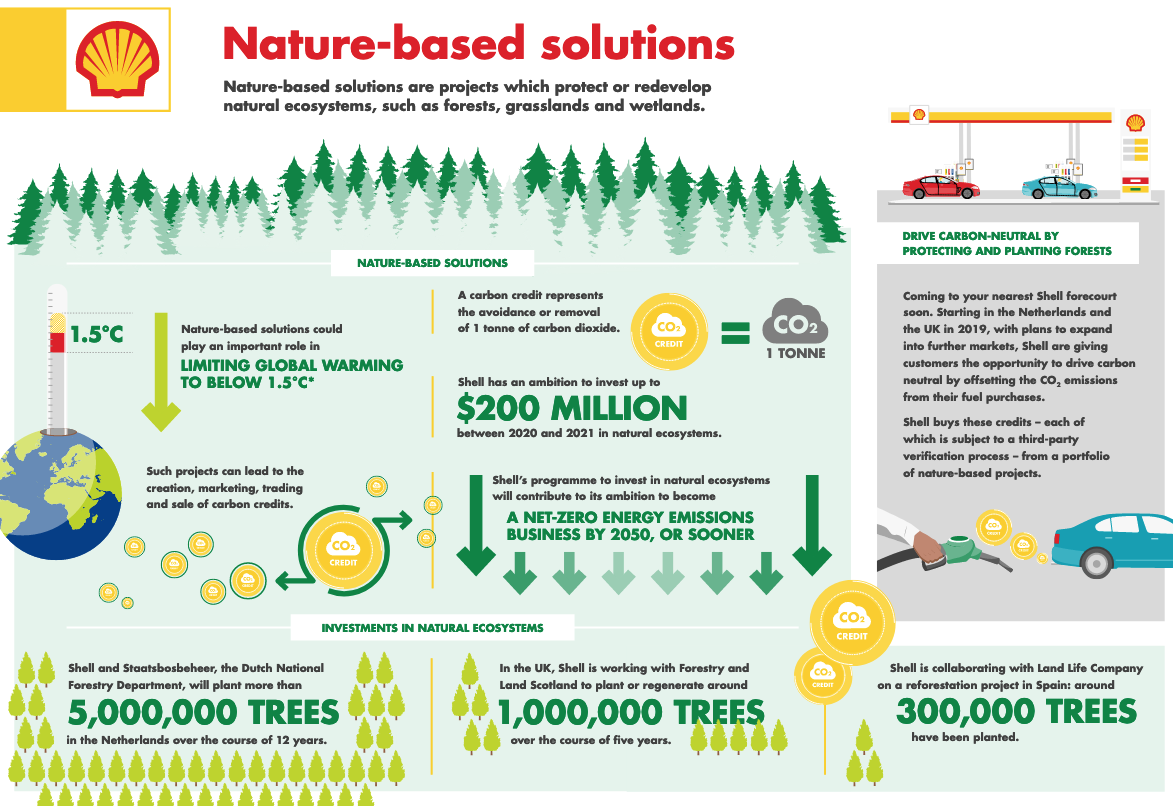

Reforestation and other nature-based solutions, including tree planting initiatives in areas that previously had no forested land (afforestation), restoring destroyed or degraded ecosystems, restoring marine or coastal habitats, and implementing green infrastructure projects.

For example, Shell oil, as part of its net zero pledge, plans to invest $300 million over three years in natural ecosystem-based initiatives, primarily in the form of reforestation projects. L’Oreal Groupe, in partnership with experts and suppliers, has committed to balancing its residual emissions via low-carbon farming practices and sustainable forest management programs.

Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) and Direct Air Capture. These are technology-based solutions that involve capturing CO2 from business operations and storing it through various measures.

Microsoft, for example, is paying Swiss direct-air-capture startup, Climeworks, to remove the equivalent of 11% of the annual CO2 emissions from Microsoft’s value chain.

Alternative fuels, including biofuels, green hydrogen, and sustainable aviation fuels. The IATA, for example, estimates that SAF “could contribute around 65% of the reduction in emissions needed by aviation to reach net–zero in 2050.”

Carbon market offsetting mechanisms that allow companies to offset their polluting activities through the purchase of carbon credits.

The Corporate Net Zero Climate Pledge: Pitfalls

In a mad dash to demonstrate they’re part of a climate-focused solution, many companies have resorted to greenwashing tactics in producing their net zero plans. Critics have gone so far as to render the net zero plan an utterly useless mitigation tool that reveals a “dangerous lack of critical analysis“.

Lack of a Standardized Process

The mishmash of net zero plans that companies have released makes it difficult to assess and analyze their viability. Many plans are created in-house, allowing companies to tailor programs that look good on paper but make scant contributions to meaningful emissions reduction.

ExxonMobil’s net zero climate pledge, for example, sounds ambitious, but it doesn’t include indirect (Scope 3) emissions from upstream and downstream activities. These are significant, representing about 90% of ExxonMobil’s current emissions. An omission of Scope 3 emissions, therefore, renders ExxonMobil’s net zero plan ineffectual.

The use of carbon intensity metrics, rather than focusing on the reduction of absolute emissions is another way to obscure rising emissions. For example, Shell has pledged to reduce its carbon intensity by 6-8% by the end of 2023 but plans to increase its oil and gas production by 3% each year.

BP’s net zero “ambition” looks more promising, with its inclusion of Scope 3 emissions in its net zero goals, but has deftly excluded more than 40% of its oil and gas operations from its stake in the Russian energy giant, Rosneft.

Most importantly, none of the oil majors has committed to cutting oil and gas production–undoubtedly the most effective way to reduce emissions and one called for by The International Energy Agency.

A Lack of Urgency

With the planet hurtling towards a perilous state of global warming, the time to act is now, but most corporate plans do not address the urgency of the climate crisis.

According to a recent report by Accenture, only 9% of the 1,000 net zero plans studied are on course to meet business goals by 2050. The report concludes that most companies will need to double the pace of emissions reduction in the next decade, and then accelerate further to achieve their net zero goal.

This lack of urgency is summed up best by former IPCC chair Robert Watson and his co-authors, who write in their criticism of the net zero climate pledge that “in practice it helps perpetuate a belief in technological salvation [yet] diminishes the sense of urgency surrounding the need to curb emissions now.”

Flawed Mechanisms

Carbon Capture Technologies

Some of the tools for offsetting emissions are not as effective as advertised. Take a look at carbon capture and sequestration technologies that many fossil fuel companies–claiming that these projects offset emissions from operations–have added to their respective net zero toolkits.

Shell, for example, plans to become a net-zero emissions energy business by 2050 by “reducing emissions from our operations” and “capturing and storing any remaining emissions using technology or balancing them with offsets.” Yet its carbon capture and storage facility in Alberta, Canada, appears to emit more carbon than it is capturing. A recent report by Global Witness found that while the facility captured 5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide between 2015 and 2019, it ended up emitting 7.5 million tonnes of greenhouse gases in the same timeframe.

The problem with these fledgling CCS technologies is not just efficacy. It’s also one of scale. In their present form, these carbon capture projects are unable to absorb the staggering volumes of emissions. Indeed, to date, carbon capture projects capture less than 0.1% of global emissions.

Just as recycling gives plastics producers an excuse to keep producing plastic, CCS allows oil and gas industries to keep extracting and producing more oil. And there’s the rub. In its current (and most likely, future) state, CCS cannot be held up as the best solution to decarbonization, particularly when over 80% of carbon captured to date has been used to extract more oil. That’s right, CCS is being used primarily for “carbon-emitting oil extraction that wouldn’t have otherwise been possible.”

As The International Energy Agency has pointed out: “It is important to note that carbon removal technologies are not an alternative to cutting emissions or an excuse for delayed action.”

Additional Mechanisms

Other removal mechanisms may be more established than CCS, but again, scale is a factor. Cathay Pacific Group’s plan, for example, includes the purchase of 1.1 million tonnes of SAF over a period of 10 years, but this represents only 2% of its total fuel requirements.

Like CCS, many of the emerging alternative fuels are based on unproven technologies that simply can’t compete with the scale and cost needed to replace their fossil fuel counterparts.

Even nature-based solutions face challenges, including the lifecycle of a nature-based project that can take longer than needed. These projects face the added risk of being obviated by a whole host of natural and manmade disasters: wildfires, disease, illegal logging, floods, and extreme weather events, to name a few.

Companies are increasingly relying on carbon markets to offset emissions, but to date, carbon credits operate in an unregulated market. With little oversight of this rapidly burgeoning market, it will be difficult to assess the viability of offset projects to absorb emissions, not to mention proper accounting of offsets that should only be used once.

Should Companies Scrap Their Net Zero Pledges?

Corporate America’s recognition that it must decarbonize is a step in the right direction, but the temptation to use net zero pledges to delay climate action is a significant problem.

The bottom line is that companies must prioritize the elimination of emissions from their operations. Only residual emissions that are impossible to eliminate should then be offset via substantive measures.

What’s needed to bolster net zero pledges? Some of the improvements to these plans include:

- Prioritization of the elimination of emissions before using net zero offsetting tools, which should only be used for residual emissions that are impossible to remove.

- Prioritization of reducing absolute emissions rather than focusing on carbon intensity metrics.

- Acceleration of emissions reduction and abatement to meet net zero goals by no later than 2050, preferably sooner.

- The creation of a comprehensive, standardized greenhouse gas auditing tool that establishes an accurate accounting of the baseline footprint of emissions across a company’s value chain.

- A more standardized approach to carbon removal that will allow for apples-to-apples comparisons among companies and sectors.

- More objective oversight of plans and their progress. The Net Zero Tracker and Transition Pathway Initiative are two organizations that provide in-depth analysis of hundreds of publicly-traded companies, but more robust tracking measures are needed.